Step outside the city and into the trees, and New York starts to change. Somewhere beyond the boroughs, beyond the Thruway and strip malls, the land begins to rise and fall again. And then you hit it—the thick wall of green, where the air sharpens, the shoulders drop, and the sound of traffic is replaced by the hiss of wind through spruce. You’re in the Adirondacks now, and the transformation is total.

Hidden Gems of Adirondack Park

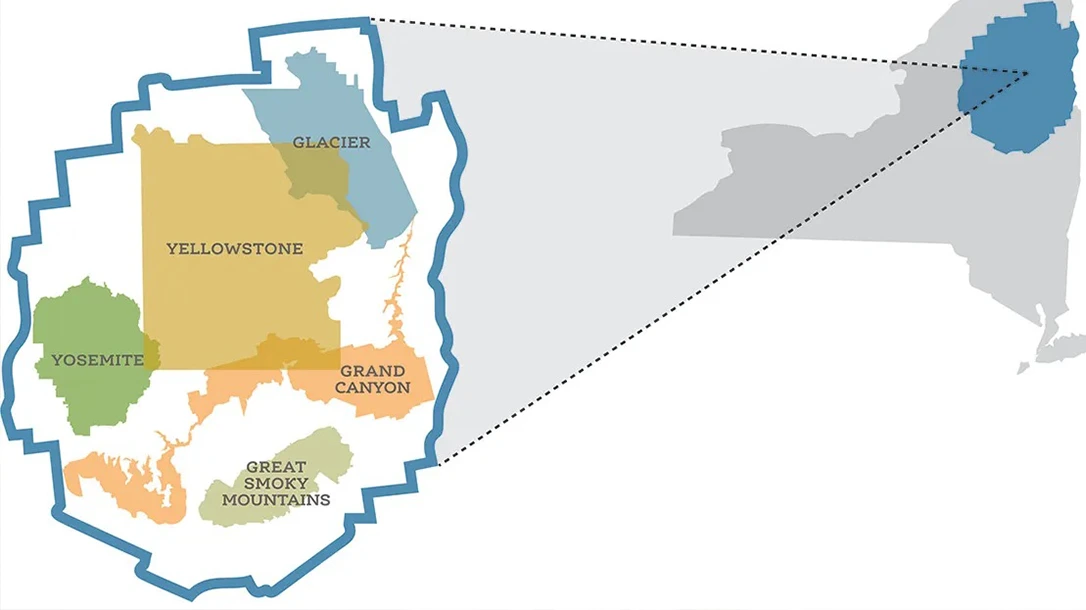

Most people think they know New York. They picture glass towers and yellow cabs, Wall Street and Broadway. But that’s a fraction of the state, and the least wild part. Six million acres sprawl across the northeastern corner—an expanse of forest, river, and granite spine that has quietly stood as one of the greatest environmental protections in U.S. history. It’s bigger than Yellowstone, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, and Glacier National Parks combined. Totaling more than nine thousand square miles, it’s larger than its neighboring state of Vermont. You could fit Rhode Island and all of its waterways into it over six times.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

And yet, it’s not a national park. It’s not fenced, ticketed, or neatly curated. The Adirondack Park is a bold American experiment—public and private land braided together, stitched by hamlets and homesteads, with strict constitutional protections that say, simply, it shall remain “forever wild.” That phrase, written in 1894, has helped preserve a staggering natural cathedral for well over a century.

A Living Monument to Wilderness

The Adirondack Mountains are ancient—once as tall as the Rockies, but now softened by time. They’re part of the Canadian Shield, not the Appalachian range, and rise like a worn fist of rock that was never fully tamed. The park is home to more than 3,000 lakes and ponds, 1,200 miles of rivers, and over 2,000 miles of hiking trails—more than any other state park system in the country.

It’s a place where black bears still roam, moose slip through wetlands, and loons call across glassy water at dusk.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The climate here is no joke. Winters come hard and early, icing over the High Peaks and turning the valleys into storybook snow scenes. Summers are warm but rarely hot, and the shoulder seasons carry a kind of haunted beauty.

Fall, in particular, is divine—fire-orange ridgelines and crisp air that smells like pine and woodsmoke. For the patient and prepared, the Adirondacks give back more than most places ever could.

Layers of History

This is not untouched land, even if it sometimes feels that way. The Adirondacks have a long and complex human history—home first to Indigenous peoples, such as the Mohawk and Algonquin-speaking tribes, and later, a region shaped by trappers, loggers, miners, and hermits. The name “Adirondack” itself is thought to be a Mohawk term meaning “bark-eater,” once used to describe rival tribes who were said to survive winters eating tree bark when game was scarce.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

By the 1800s, the Adirondacks had become a proving ground for industries and adventurers alike. Logging and iron mining were brutal but vital trades. Whole towns sprang up around forges and mills, then vanished when the veins dried or the forests were stripped bare. At the same time, Gilded Age tycoons—people like the Vanderbilts and Rockefellers—began retreating to their “Great Camps,” where they could fish, hunt, and build monumental lodges of pine and stone.

Out of this duality—extraction and escape—emerged the modern park. Conservationists fought hard to stop clear-cutting and preserve the headwaters of the Hudson River. Their work led to the landmark “Forever Wild” clause, which enshrines the forest preserve in the state constitution and sets a precedent that other states and national agencies would follow. The result is a protected zone where towns exist not in spite of the wilderness, but within it.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Towns with Soul

The Adirondacks aren’t just empty space. Roughly 130,000 people live within the park’s boundaries, scattered across towns that reflect the grit and humility of the landscape. They’re not resorts. They’re real places, with sawmills and diners and general stores, and they carry the character of people who’ve chosen quiet over convenience.

Tupper Lake, for example, is home to The Wild Center, an innovative natural history museum with living exhibits and a treetop walk that makes you feel like a red squirrel on patrol. It’s a town where science and storytelling meet the needs of rural life, and where conservation doesn’t feel preachy—it feels practical.

Down the road, Blue Mountain Lake is a postcard brought to life. It’s quiet. Peaceful. However, it also features the Adirondack Museum—arguably the best window into the region’s human and natural history. The museum is situated on a slope above the lake, with buildings and exhibits that seamlessly blend into the surrounding forest and gallery. Canoes, sleds, paintings, and logging tools fill the space, surrounded by trails and viewpoints that show precisely where it all came from.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Lake George, located at the southern edge of Adirondack Park, offers a distinct rhythm—a place for families and tourists, yet still proud of its revolutionary past. Fort William Henry stands here, famously dramatized in The Last of the Mohicans, and its ghost tours and reenactments remind visitors that the Adirondacks once sat at the contested edge of empires and the frontier of our country itself.

These towns, and others like Saranac Lake, Keene, and Indian Lake, carry more than just cabins and coffee shops. They carry a worldview—a respect for place and people that feels increasingly rare.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Ghosts in the Granite

The mountains here hold stories. Some are quiet—etched into trail signs and journal entries. Others are louder, whispered through folklore and passed around fires.

Tales of hermits are widespread. No wonder. This place has a gravity to it that draws solitude-seekers. One of the most famous was Noah John Rondeau, a self-described “Mayor of Cold River City (Population 1).”

He lived alone deep in the western High Peaks during the 1930s and ‘40s, building cabins and writing journals in a cipher of his own creation. Rondeau wasn’t a crank—he was witty, social when he chose to be, and oddly civic-minded, even in solitude. He greeted occasional hikers with warmth and posed for photographs, a flannel-clad philosopher who managed to turn isolation into identity.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Inspiring Authors

Further east, near Twitchell Lake, another kind of solitude took shape. In the early 1970s, Anne LaBastille, an ecologist and fierce advocate for wilderness preservation, built a one-room cabin by hand. She named it “West of the Wind.” With no running water or electricity, she lived there on and off for decades, writing Woodswoman, a landmark memoir that became a beacon for independent women and wilderness lovers alike.

Her writing wasn’t romantic—it was real, thorny, and hard-earned. She spoke of hauling water in winter, of listening to loons through thin walls, and of navigating the fine line between freedom and loneliness. That tension remains in every creak of her floorboards, still standing today under preservation care.

And then there were the ones who left no books behind. Miners in the 19th century who blasted open the land for iron, only to vanish when the veins gave out. Whole settlements like Tahawussprung up around forges and disappeared into the trees once the industrial age moved on. In places like Lyon Mountain, their tools still rust beneath the leaves—giant ore carts, pulleys, and chisels now consumed by moss and time.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

There were loggers, too—tough men who felled white pine with crosscut saws and floated timber down swollen rivers. Their camps were crude, their days brutal. And yet some stayed. Built cabins. Raised families. Named ponds and ridges after themselves. Some are buried on the very land they once cleared. You might walk past their grave markers and never know it.

Rich in American History

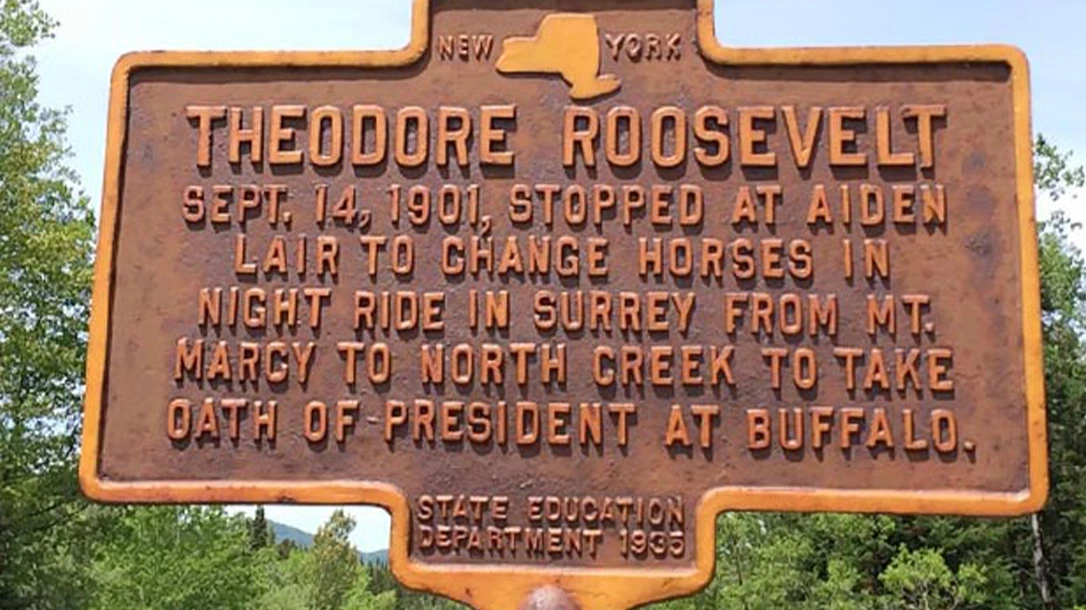

Even the giants of American history have walked these woods. Theodore Roosevelt, a passionate naturalist and champion of wilderness conservation, famously hiked the High Peaks—including Mount Marcy—and was deep in the Adirondacks when he received word that President McKinley had taken a turn for the worse. He made a midnight dash by wagon from Tahawus to North Creek to assume the presidency.

The rugged terrain that tested him would later inspire his legacy as the father of America’s National Parks. Ulysses S. Grant, the stoic Union general and 18th President, spent his final days just outside the Blue Line at Mount McGregor in Gansevoort, where he completed his memoirs on the porch of a cottage overlooking the southern foothills. He died there in 1885, surrounded by family and pain—but also by peace, held by the quiet green cradle of the Adirondacks.

One of the most chilling and tragic echoes in Adirondack history is the murder of Grace Brownon Big Moose Lake in 1906. A young factory girl lured into the woods by her lover, Chester Gillette, under the false promise of marriage, only to be struck down and left to drown. The case captivated the nation, inspiring novels like An American Tragedy and cementing the region in the American Gothic imagination.

A Name Forgotten

Of course, there are the unknowns—those who came to these woods for reasons lost to time. The half-frozen boot print was found ten miles from a trailhead. The decaying canoe was chained to a stump. The old diary tucked into a barn loft with just a name and a few sentences: “Snowed again. Out of tobacco. But not bad.”

These are the ghosts that linger. Not in the supernatural sense—but in the way that the forest holds memory. The Adirondacks are full of them, if you know where to look. A rusted hinge. A scatter of blue glass. The shape of a road once cut and reclaimed by root and fern. These details don’t shout—but they whisper. And if you listen, really listen, they’ll tell you more about what it means to live deliberately than any textbook ever could.

This is a land of beginnings and endings. Of people who came to vanish. Or maybe to be found.

The Artists of Adirondack Park

For generations, the Adirondacks have pulled at the hearts of artists—painters, poets, photographers, and pipe-smoking essayists alike—each trying in their own way to capture the impossible. Light dances differently here, filtered through balsam and mist. The silence isn’t empty; it hums. And for those attuned to it, the Park offers not just a subject, but a medium.

Rockwell Kent came here often, known for his bold, graphic landscapes and the near-mystical solitude he found in these hills. His paintings weren’t romanticized—they were honest, muscular, shaped by the wind and the sharp edge of the seasons. Kent’s work helped codify an aesthetic of the American wild, one that was as much about endurance as it was about beauty.

Harold Weston, a lesser-known but no less vital voice, spent years painting in the High Peaks, sometimes with bare hands when his brushes froze. His oils—thick with texture and conviction—aren’t just landscapes. They’re testaments. Weston believed the mountains had a moral power, that by painting them faithfully, he could “affirm life.”

Writers, too, have been shaped by this place. Sigurd Olson, though more closely associated with the Boundary Waters, visited the Adirondacks often and spoke of them with the same reverence he reserved for the canoe country of the north. His prose is clean, reflective, always pointing back to the soul’s need for stillness.

Modern creators still come. Some carry cameras, others sketchpads or notebooks. Some never share what they make. That’s part of the magic— Adirondack Park doesn’t demand output. It invites absorption. You don’t go to the Adirondacks to become someone new. You go there to remember who you were, before noise.

War and Wilderness

The Adirondack region played a crucial role in early American conflict. During the French and Indian War, it served as a strategic corridor between British and French holdings and was the site of several major forts and skirmishes. Fort Ticonderoga, formerly known as Fort Carillon, played a pivotal role in multiple conflicts. Its capture by Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold in 1775 provided the Continental Army with a significant morale boost and access to cannons that would be used during the Siege of Boston.

Saratoga, just south of the park’s boundary, was the site of the turning-point battle of the Revolutionary War, thanks to Daniel Morgan and his Riflemen. It’s not technically within the Adirondacks, but its victory changed the shape of American destiny—and the forests north of it provided the landscape through which armies moved, and where militiamen knew every bend in the river.

Fort William Henry, at Lake George, was the site of a horrific battle and betrayal, where surrender turned into massacre. Today, it stands not only as a reenactment site but also as a deeply educational resource for families seeking to understand the cost of empire, freedom, and liberty.

The Return of the Pipe-Smoking Poet

I’ve traveled this park with a revolver on my hip, a pipe in my pocket, and a camera slung over my shoulder. I’ve hiked the trails with my son, with friends, with silence. I’ve driven miles just to stand beside a frozen lake, or wait for fog to lift from a trailhead. I’ve written articles in lean-tos and taken phone calls beside creeks. And every time I return, the Adirondacks manage to show me something I hadn’t seen before.

It’s not nostalgia that draws me here, though that plays a part. It’s something older than memory—a rootedness. The kind that reminds you you’re small, but not insignificant. That the land was here long before us, and will remain long after.

There’s a moment—if you’ve spent any time in this park, you’ve felt it. Maybe it’s early morning mist over a pond. The hush of snow in the evergreens. Or the long call of a Loon over still water.Or the breath you didn’t know you were holding when the wind stops and the world stands still. That moment is the magic.

Meaningful and Mysterious

That’s what the Adirondacks are to me. Not just a location, but a rhythm. A place where nature, history, and soul converge. Where you go to listen, not just to speak. Where you remember what it means to feel grounded—not just to the earth beneath your boots, but to the person you want to be when you walk out of the woods again.

Adirondack Park is huge, and so is this editorial… I’ve covered a lot and missed a great deal. Come visit upstate NY and leave the city for the Metropolitans. This is the NY I love, and I wish everyone could see it. It’s a beautiful and majestic space filled with wonder and natural beauty that you have to see in person. Let me know when you visit, and I’ll meet you for a hike. If you stop by the Blue Mountain Adirondack Museum, let them know Mitch sent you. Explore safely.