As a former theater technical director and front-of-house audio engineer, I’ve spent much of my life chasing the sublime qualities of sound. I’ve sculpted low-end punch until it danced in the chests of sold-out crowds and mixed vocals to float just above the chaos, making the artist feel as if they were whispering directly into each audience member’s soul. At its best, sound is transcendence. It taps into memory, identity, and emotion. It builds cathedrals of feeling in midair.

But sound is a two-edged blade. It can build a memory—or shatter one. It can immerse or overwhelm. And lately, it’s become increasingly clear that sound—purely acoustic energy—is not just an emotional tool or artistic device. It’s a weapon.

To understand how sound is used offensively in military operations and crowd control alike, we first need to understand what sound is, how the human body receives it, and why certain frequencies and volumes bypass the intellect and go straight to the nervous system.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

What Sound Really Is

At its core, sound is vibration—a wave of pressure moving through air (or another medium) until it collides with a receptor, like your eardrum. That wave has two primary measurable characteristics: frequency and amplitude.

Frequency, measured in Hertz (Hz), determines pitch—how high or low a sound is perceived to be. Humans typically hear frequencies ranging from 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz (20 kHz), although sensitivity declines with age. Low frequencies, like sub-bass rumble, are felt as much as they’re heard. High frequencies, like the hiss of a cymbal or the screech of a whistle, can become painful or shrill at high volumes.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Amplitude, on the other hand, is about intensity—the perceived loudness of a sound. It’s where we begin exploring concepts such as decibels (dB) and sound pressure level (SPL). And this is where most people get confused.

Decibels vs. SPL

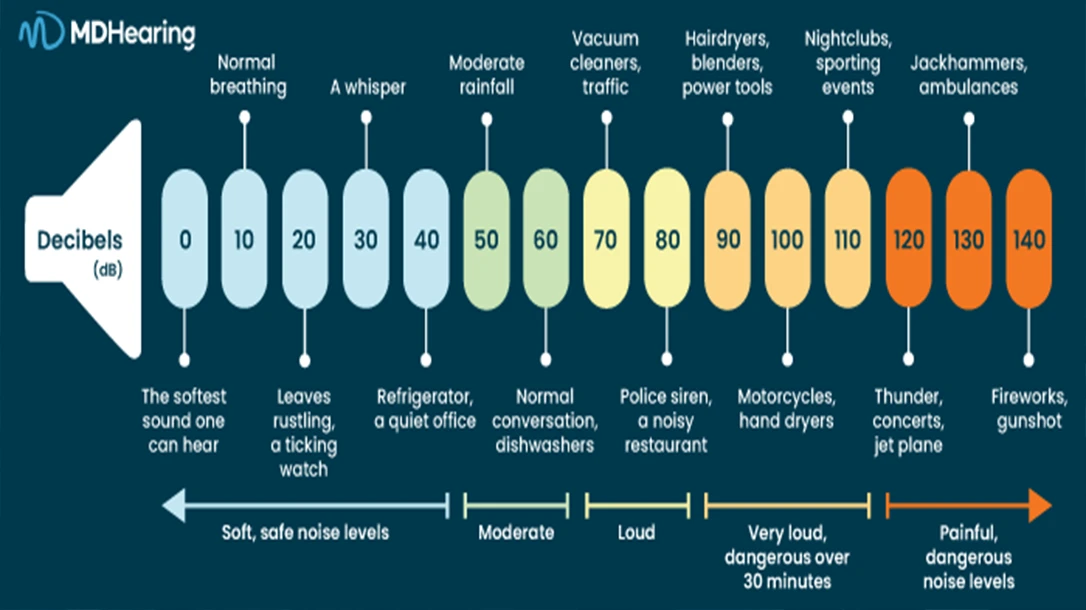

The decibel (dB) is a logarithmic unit, which means each increase of 10 dB represents a tenfold increase in sound intensity. A sound measured at 80 dB is not “twice as loud” as one at 40 dB—it’s 10,000 times more intense in terms of raw acoustic energy. This exponential scale is why small differences in dB readings can represent massive changes in the human experience.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

But decibels are only meaningful relative to something else. That’s why we often specify SPL—Sound Pressure Level—when we talk about real-world sound. SPL is decibel-based, but it’s anchored to a reference pressure level: specifically, 20 micropascals, the threshold of human hearing. So when we say something is “85 dB SPL,” we mean it’s 85 decibels louder than the quietest sound a typical human ear can detect.

SPL doesn’t just determine loudness. It determines what the body can tolerate. Prolonged exposure to sounds above 85 dB SPL can cause hearing loss. A 100 dB concert is pushing the limits of safe listening for extended periods. A 120 dB jet engine at close range can cause instant hearing damage. At 140 dB and above, you’re flirting with pain, disorientation, and in extreme cases, internal trauma.

Which brings us to how sound stops being art and starts becoming a weapon.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Sonic Weapons

The most well-known offensive sound devices in recent memory are LRADs, or Long Range Acoustic Devices. These are directional sound cannons used by police and military units worldwide, capable of blasting controlled beams of sound at over 150 dB SPL for hundreds of meters. For comparison, 150 dB is not just loud—it’s dangerously loud, enough to rupture eardrums or induce nausea.

Unlike loudspeakers at a concert, which diffuse sound over a wide area, LRADs are highly directional. They use an array of transducers to project a focused “beam” of acoustic energy. Think of it like a spotlight made of sound: if you’re in the beam, you get hit full-force. If you’re standing next to it, you might barely hear it.

This makes LRADs particularly appealing for crowd control, where law enforcement can target specific groups without blanketing an entire area in high SPL. The sound itself is designed to be unbearable—high-pitched, piercing, and physically disorienting. It exploits the human body’s built-in defenses: vertigo, nausea, and pain.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

In 2009, Pittsburgh police deployed LRADs during the G20 protests, marking one of the first high-profile domestic uses. Protesters reported hearing loss, migraines, and lingering ear damage. Since then, LRADs have made appearances in numerous law enforcement toolkits—often under the label of “non-lethal” compliance.

But LRADs are only the start.

Frequencies That Control Behavior

Not all sonic weapons rely on volume. Some use specific frequencies to create psychological or physiological effects.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

For example, infrasound—sound waves below 20 Hz, beneath the threshold of human hearing—has been studied for its ability to induce anxiety, unease, and even hallucinations. These frequencies can resonate with internal organs, especially at high SPL, causing discomfort without any audible cue. You don’t hear infrasound. You feel it.

On the other hand, ultrasound—above 20 kHz—has been utilized in various military and industrial applications. It doesn’t travel far in the air, but it can cause tissue heating at high intensity. Some directed energy weapons use ultrasound in combination with other tech to deliver pain or confusion in tight bursts.

Even music itself can be weaponized. The U.S. military famously used loud rock and heavy metal—including Metallica and Nine Inch Nails—to torment detainees at Guantanamo Bay. In other cases, they’ve used repetitive pop songs like “Baby Shark” or “I Love You” from Barney & Friends to drive out barricaded suspects or demoralize prisoners. The tactic here is less about pain and more about psychological fatigue—a kind of sensory waterboarding.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Crowd Behavior

Sound doesn’t just act on individuals—it alters the dynamics of entire groups. In crowd control scenarios, high-decibel sonic devices can disrupt cohesion, trigger panic responses, or disperse groups that might otherwise organize together. LRADs and similar devices don’t just disperse—they disorient. They fracture rhythm, communication, and leadership in a mass gathering. But the flip side is equally telling: sound can also be used to shape and manage energy non-violently.

Police departments have played calming music to de-escalate tensions at protests. Retailers use classical music or specific tempos to discourage loitering. Stadiums build momentum through bass and tempo. Whether it’s chaotic or controlled, sound is one of the most powerful crowd influencers we have, because it speaks to the nervous system faster than reason ever could.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Legal Gray Zone of Sonic Force

While sonic weapons like LRADs are marketed as “non-lethal,” their legal status is far from clear. In the United States, there’s no universally accepted standard defining how and when they should be deployed, and very little case law governing their use.

Civil rights groups have sued municipalities for excessive force, citing permanent hearing damage and misuse of crowd control tools. Internationally, the legal landscape is even murkier. Sonic weapons don’t fit neatly under chemical, kinetic, or directed-energy classifications in most humanitarian frameworks, which makes them hard to regulate. That legal ambiguity creates room for quiet abuse, because once something falls outside the rules, it tends to fall outside accountability, too.

Why Sound Is So Effective

What makes sound so potent isn’t just the physics—it’s the way the human brain is wired. We don’t just process sound through our ears. We feel it in our bones, our gut, our nerves.

The brain’s limbic system, which controls emotion and survival responses, is highly reactive to sound, particularly sudden, high-frequency, or high-volume sounds. That’s why a smoke detector or a baby’s cry can jolt you awake in ways visual stimuli never could.

Sound bypasses our intellectual defenses. It hits viscerally. That makes it a powerful communication tool—and a terrifying weapon when misused.

Civilian Applications, Questionable Ethics

Even outside of military use, sound-based deterrents are appearing more frequently in public life. In some cities, “Mosquito” devices have been installed in parks and transit stations to deter loitering by emitting high-frequency sounds only audible to younger ears. The goal is to make the space uncomfortable for teenagers without affecting adults.

On paper, it’s a passive way to manage space. In reality, it raises huge ethical questions about surveillance, discrimination, and non-consensual bodily manipulation. We’re not just talking about signs or fences—we’re talking about using invisible force to shape behavior.

That’s the common thread with offensive sound. It crosses the line from communication to control. And once that line is crossed, it’s difficult to draw back.

The Edge of Immersion

Sound has always been powerful. As an audio engineer, I’ve seen firsthand how carefully tuned frequencies and dynamics can bring thousands of people into emotional sync. That’s what makes the weaponization of sound so chilling. It takes something fundamentally human—our sensitivity to vibration, rhythm, and tone—and turns it against us.

We tend to think of violence as kinetic: fists, bullets, batons. But violence can be acoustic, too. It can be disorienting, destabilizing, and invisible. As technology advances, the line between immersive experiences and sensory overload will only blur further.

The challenge for those of us who understand the power of sound is to remain vigilant about how that power is used. Whether behind a console or under the weight of policy, we’re responsible for asking the right questions.

What is this sound doing? Who is it doing it to? And who decides?